The Malta Railway – ‘Golden Years’

The Maltese economy was slowing on the rise when in fact it was with the opening of the Suez Canal back in 1869, that the respective economy was pushed forth, so to say that it left a big impact and lead to the term known as the ‘Golden Years’ phase between the 1870s-1890s. This time showed a considerable increase of shipping towards the Mediterranean from multiple countries including Australia and Russia. (Rigby,1970)

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 made Malta’s geographic position in the centre of the Mediterranean very important to shipping movements

Due to the advancements of the ‘Golden Years’ phase, came also a higher interest in the engineering works and hence the development of building railway. (Rigby,1970) A new means of transportation for Malta.

Back in those days, a journey from Valletta going to Notabile (Mdina) would take between two to three hours by horse carriage costing 7 or 8 shillings. Hence the introduction of a railway system would have surely presented improvements in travel time as well in travel costs. In the early days, the local train was known as ‘’il-vapur tal-art’’ (ship on land) as well as ‘’landsteamer’’. (Rigby,1970)

The railway was originally proposed by the entrepreneur J. Scott Tucker back in 1870 but was further developed via the ‘Malta Railways Company Limited’. The company was formed back on 12th June 1979 and had to carry out negotiations with the Home Government, Colonial Office and the Government of Malta at the time. With all this led the opening of the railway on 28th February 1883. (Rigby,1970)

The Inauguration of the Malta Railway on 28th February, 1883 at Notabile Railway Terminus

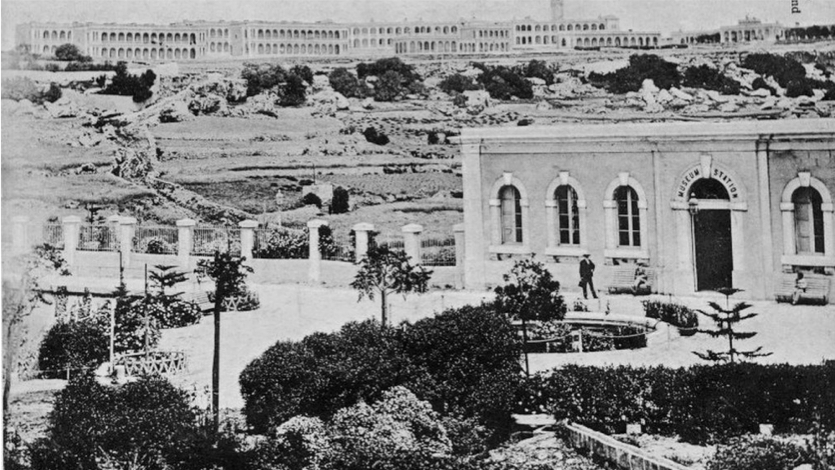

The Railway’s management from a private and limited company was indeed a short one. The Malta Railway Company Ltd went into bankrupt and on 1st April 1890 the Railway ceased to a stop. The Government took matter to the Court and won the ownership of the Railway. After the expansion as well as the improvements to the system, the Railway was re-launched on the 25th of February 1892. (Rigby,1970) In 1890 the Government took over the Railway as specified by legally. The railway was extended towards Mtarf. A tunnel was dug from Notabile Station, partly undergoing Mdina to the Valley between Mdina and Mtarfa. A new Station terminus was built and named Museum since it was very close to the Roman Villa Museum. This was to service the Military personnel residing at Mtarfa Barracks, also the staff and visitors to the Royal Naval Hospital at Mtarfa.

The Malta Railway was to keep operating for the next 39 years until new more improved means of transport systems were introduced, rendering the Railway system out-of-date. (Rigby,1970)

Brigadier Bernard L. Rigby was a young soldier who was serving with his regiment in Malta in the 1930s. He had walked the line from Valletta to Museum (with the exception of tunnels and the odd embankment) when the infrastructure was still in reasonable condition and one could still feel the line. More then 30 years later Rigby wrote his book, ‘The Malta Railway’, which was first published by Oakwood Press 1n 1970. The revised second edition was published by Oakwood Press in 2004. Brigadier Bernard L. Rigby’s publication, The Malta Railway was dedicated to The Citizens of Malta G.C.

The Journey

The Railway crossed the island from Valletta Terminus to Museum Station which was situated in the valley between Mdina on one side and Mtarfa on the other side.

There were several Railway Stations and stops that the train made along its route.

The Railway Route:

- Valletta Terminus

- Floriana Railway Station (underground)

- Hamrun Railway Station (Railway Complex)

- Msida Platform

- Birchircara Railway Station (Central Station)

- Balzan San Antonio Platform

- Attard Railway Station

- Attard San Salvatore Platform

- Rabat Notabile Railway Station

- Mtarfa Museum Railway Station

With the sound of the guard’s whistle and the ringing of a handbell (as often in Victorian England), the train used to leave the Valletta station and lead to its next stop in Floriana. (Rigby,1970)

The Floriana stop was not as popular as other stops. Economically it did not make sense for people to use it to go to Valletta and majority preferred starting their journey from Valletta should they have wanted to visit Notabile. Besides this, Florianas’ entire platform happened to be well below the ground and proved to be unappealing for a lot of people hence why it was infamous. (Rigby,1970)

The Floriana depth though proved to be of importance especially in World War II when the tunnel served as an air raid shelter.

The next stop was Hamrun. The platform at the time was settled into a background of trees. It was also known to be the engineering headquarters. It had multiple workshops. There were two platforms and on the southern platforms there were waiting rooms, ticket booths and luggage offices. (Rigby,1970)

Msida was about 1.7km far from Hamrun. The Msida platform was not as eccentric as other platforms and was termed as the ‘Halt’- which by definition is smaller than a station. In particular of these Halts, the travellers waiting to go on the train had to signal the train to stop. The ones travelling on the train had the guard arrange their stop in these ‘intermediate stations’. A particular timetable had written: ‘with the exception of the 4.30, 5.20 and 6am and the 5.10 and 5.30pm all other trains will stop at any intermediate station at the request of the passengers’. (Rigby,1970).

There have been times were these some unpopular stations (unlike the well known ones) where often not included in the train timetable. This includes the stop at St.Venera. There have been multiple sources that have contradicted one another on the existence of such a halt. In fact the timetable at the beginning of its services mentioned : Valletta, Hamrun, Msida, Birkirkara, San Antonio, Attard, San Salvatore and Notabile. The Management in 1910 mentioned there were six stations but in 1924, timetables were showing only Valletta, Hamrun, Birkirkara, Attard and the Museum (with Balzan and San Salvatore in footnotes). The rest of the stations except Floriana were probably referred to as ‘Halt’. (Rigby,1970)

A 1943 view of the Floriana tunnel in use as an air raid shelter (The Malta Railway, B.L. Rigby)

Birkirkara (Birchircara) was the next stop after Msida. This station was referred to as Birchircara. The language used was English apart from the actual place/platform names. The first timetables of this Railway were in Italian and were changed to English along the years. The Maltese language to this day is known to be a mixture of the Maltese ancestries and the Italian influence is still heavily noted in the Maltese vocabulary. (Rigby,1970)

Birchircara station was on the south boundary of the town. A church was situated at the area of the station. The respective station was fully decorated with flower beds, palm trees and seats in the shelter of the wall for a nice catch up in the warm sun. Elaborated sun canopies extended over the platform and more flowers that were also at shoulder height on shelves. This scenery attracted numerous enthusiasts, to the point where this station was also known as a common place where locals met and not necessarily just to catch the train. The manager Nicholas Buhagiar realised the potential of the place and added on extra trees such as lemon and orange trees and in 1912 he produced large urns for flowers, some of which are still present to this day. (Rigby,1970)

At the Birchircara Station there were also water reservoirs to replenish the water tanks on the locomotives.

The Birkirkara train station was then used as Government offices once the station was brought to a close. During the time, it was a sudden change to the usual site at the area but through the years the area was renovated to maintain the picturesque vision of the time when the train was working. (Rigby,1970)

From Birkirkara, the train kept going to Balzan. Balzan was another ‘Halt’ just like Msida and so was the next stop, San Antonio. At San Antonio, in the early days, there were tamarisk and carob trees that offered a pleasant scene and complimented the gardens of the San Anton Palace, which indeed was mostly frequented by visitors. (Rigby,1970)

The train would then approach the Attard station, which was felt as if it was the firsts of uplands stations. Attard station was very similar to the Birkirkara one. It had a lot of open space with flower beds and palm trees. Likewise, it also had a canopy extending from the train station with internal offices and ‘Attard’ on the entrance building.(Rigby,1970)

The train proceeded from Attard to San Salvatore, which was indeed another ‘Halt’. San Salvatore also offered a lot of open space. Back in time, San Salvatore was seen as ‘’a favourite and nearby country spot for town-dwellers in holiday festive mood’’. It was also a halt that was constantly used by patients, hospital staff and visitors of the mental hospital, close by the station that was marked on all maps as the ‘Lunatic Asylum’. (Rigby,1970)

The train slowly made its way to the Notabile station. This part of the journey ‘’was the longest on the line between stations’’. The station was made up of one platform. ‘’It dealt largely with workers of many sorts, travelling to their likelihoods in both places from their homes in the Valletta conurbation. If the work was in the old city you climbed the upward stairway and entered through the magnificent gate-bridge’’. The train journey to the town (The Museum) from Notabile was a major advancement in construction achievement. It pierced the hill on which stands the old capital of Mdina. (Rigby,1970)

The Museum, and final station stop, was in the middle between Mdina and Wied il-March. The military barracks were on the opposite side of the valley and this explains the reason why the train was used by military soldiers. It was close to their Headquarters. The Museum station was designed by Mr. Nicholas Buhagiar. He created a park-like area with use of his favourite circular flower beds. The central door of the station was welcomed with ‘Museum Station’ painted words. (Rigby,1970)

Locomotives

The Malta Railway had 10 locomotives.

| EngineEntine Type | Type | Maker | Maker’s No | Date |

| 1 | 0-6-0T | Manning Wardle & Co. Ltd., Leeds | 842 | 1882 |

| 2 | 0-6-0T | Manning Wardle & Co. Ltd., Leeds | 843 | 1882 |

| 3 | 0-6-0T | Manning Wardle & Co. Ltd., Leeds | 844 | 1883 |

| 4 | 0-6-0ST | Black Hawthorn & Co. Ltd., Gateshead | 753 | 1884 |

| 5 | 2-6-4T | Manning Wardle & Co. Ltd., Leeds | 1243 | 1891 |

| 6 | 2-6-4T | Manning Wardle & Co. Ltd., Leeds | 1261 | 1892 |

| 7 | 2-6-4T | Beyer Peacock & Co. Ltd., Manchester | 3678 | 1895 |

| 8 | 2-6-4T | Beyer Peacock & Co. Ltd., Manchester | 3852 | 1896 |

| 9 | 2-6-4T | Beyer Peacock & Co. Ltd., Manchester | 4163 | 1899 |

| 10 | 2-6-4T | Beyer Peacock & Co. Ltd., Manchester | 4719 | 1903 |

Engines Nos 5 and 6 were brought once more from the Manning Wardle. Engines Nos 7, 8, 9 and 10 were bought from Beyer Peacock of Manchester.

The Governor’s carriage at Hamrun railway complex.

Loco No 7 outside one of the Hamrun sheds shortly after delivery in

Carriages and Travellers

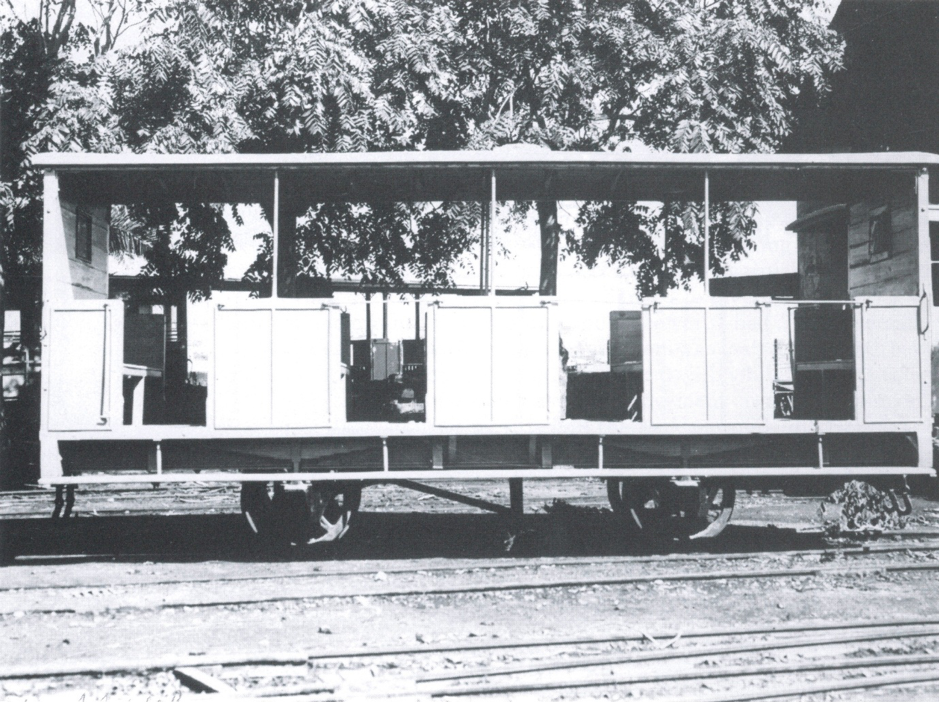

‘’There were at maximum, 33 passenger coaches, a lesser number of workmen’s carriages, and a very small number, probably less than 12, ballast wagons and platelayers’ trolleys.’’ (Rigby,1970).

There was also a Governor’s coach. This respective coach was similar to the design of the first class coaches.

The carriages were to built from the highest quality materials to resist the elements. Multiple different materials were used in the built. Such materials used were indeed timber and steel as well as Moulmein Teak for outside panelling and bottom framing and Clair White Oak for inner bottom sides, seat rails, and hoop sticks, amongst other materials.

There were multiple travellers that used the railway services throughout the years. They were used by the general public and British Military personnel, some of which were stationed at Mtarfa Barracks. Others needed to get across from one point towards another especially since the train terminated at Mtarfa which was the closest to the northern defence line of Malta. The Head Quarters were at Bingemma.

Doctors, nurses and other medical professions were also frequent travellers since along the Railway path there were numerous hospitals which also included the Naval Hospital at Mtarfa.

An interesting point here that could be mentioned related to the above is that during the Epidemic – Influenza 1918-1919, a high death toll rate was registered in the areas were the hospitals where, since naturally the death certificates were issued mostly from these respective hospitals that were indeed along the Railway line.

Other means of transport

‘’By 1904 the railway had increased its number of passengers per year from 630,000 in 1893 to 960,000. It never again reached this latter figure. The electric tramway was introduced in 1905 and by 1910 the railway figure was down to 750,000.’’ (Rigby,1970)

This new means was said to cover between Valletta, the Three Cities and Zebbug and other parts of the island that were not covered by the railway. This posed as a threat for the Government that shut down the possibility of expanding the Railway but also the Government was not too pleased of the parallel voyage offered by the Railway and the Tram from Valletta to Birkirkara. (Rigby, 1970)

In view of all that was taking place, some believed that it was the introduction of the Tramways that caused the Railway to loose commuters, others believed that the competition did not cause serious financial hardship to the Railway with some stating that the Railway was looked upon by the Government more as a social amenity rather than a commercial concern providing mass public transportation. The Railway Managers had opposed to this idea as they always tried to run it on commercial lines.

Nonetheless the private company owning the tram, surely created competition. They had more stops and could readily stop anywhere at the delight of the customer.

Little did it cross the minds of both entities that the introduction of a new concept known as, the ‘omnibus’ would force them to cease operations and wrap up their business. Built by John I. Thoryncroft and Co. Ltd. it had ultimately led to the establishment of the Malta Motor Bus Company. It was surely to expand and extend routes quickly, something that could not easily be carried out by the railway and the tramways.

With the introduction of ‘cheap chassis for internal combustion’ (Rigby1970), especially in America, as well as the establishment of the Overseas Motor Transport Co. Ltd., made it easier for the importation of vehicles. Vehicles operating in the same areas as the tram and the train created direct competition and loss of customers.

The end of the Tram and ‘Il-Vapur tal-Art’

The Tramways closed down on 15th December1929 and the Railway on 31st March 1931 due to the new and more efficient means of transport and the financial insufficiencies that followed. Whilst these two systems closed down, the Bus service flourished and introduced routes all over the island.

The remnants and memories

What remains of the Railway on our roads are the roads through which it travelled, one or two embankments, some of the Railway Stations and the memories of the Malta Railway that will live on.

In front of the Brichircara Railway Station one finds the last remaining original passenger carriage out of the 33 that the railway had. Recently the Birkirkara Local Council, with the technical expertise assistance of The Malta Railway Foundation has successfully restored this carriage and set it in place by the station platform to serve as a monument of the once upon a time when Malta had its own little railway.

The Hamrun Railway Station is used by the 1st Hamrun Scouts Group Duke of Argyll’s Own. In collaboration with The Malta Railway Foundation events to commemorate the Railway memories are held.

A number of roads, in the vicinity of the railway route, still bare a related name to cherish the memory of the Old Railway. Some of these include:

- Triq il-Ferrovija l-Qadima

- Triq il-Ferrovija

- Old Railway Track

- Trejqa Tal-Ferrovija

- Triq Il-Linja

Museum Railway Station has in recent years been restored. This station as previously mentioned, was the last stop in the route of the railway. It now serves as a restaurant/cafeteria which welcomes railway enthusiast and tourists to dine at what was once the place where commuters embarked and disembarked. The place where many started or ended their journey.